Scientists from Louisiana State University are using artificial intelligence to help predict and address water quality issues faster and more accurately, with hopes their tools could help shrink the oxygendepleted “dead zone” that develops annually in the Gulf of Mexico.

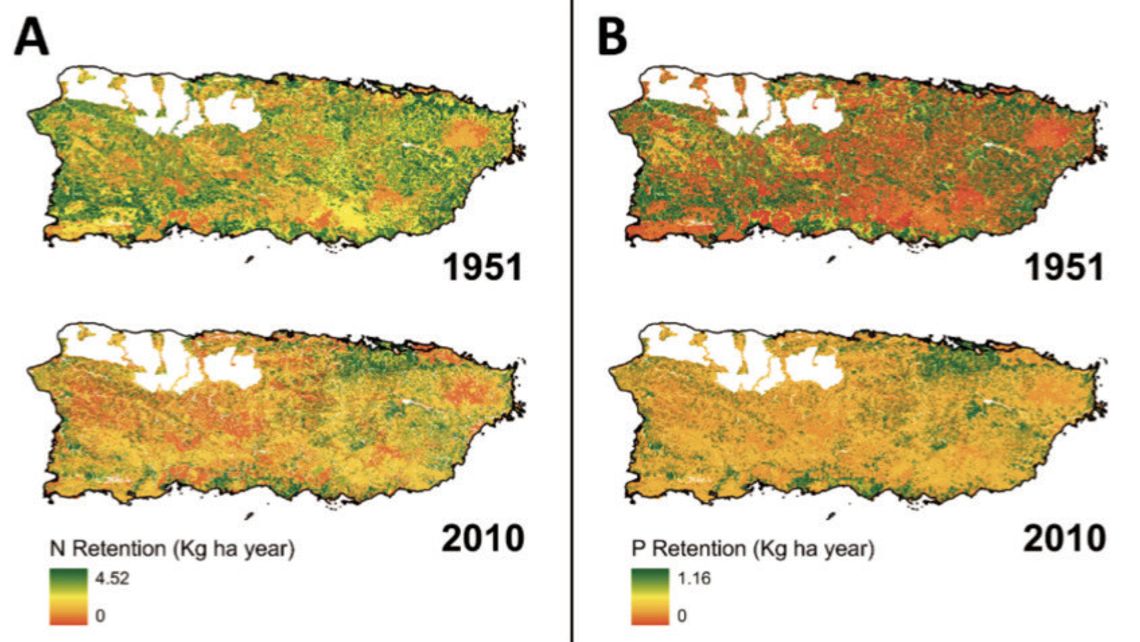

The researchers have developed an AI tool that fills in the data blanks for areas where water testing isn’t available or can’t be verified. To test their technology, they used it to predict how much nitrogen and phosphorus are present in the rivers and streams of Puerto Rico and what amounts are in the soil. The two elements are primary ingredients of agricultural fertilizers, and they can deplete the oxygen content of water by fueling algae growth.

The AI-informed models offer insight into how nitrogen and phosphorus can be retained in soil instead of washing downstream where they can fuel hypoxic dead zones.

“That’s a big difference that can also help planners and decision makers say, ‘Where do we need to restore throughout the watersheds? … How can we increase the capacity of those places that retain nutrients like this?’” said Mariam Valladares Castellanos, lead author of the paper and postdoctoral researcher at LSU. Her team’s findings were published in the academic journal Science of The Total Environment in October.

Puerto Rico, at 3,500 square miles, is relatively small when compared with the Mississippi River Basin, which covers 31 states. But Valladares Castellanos said the island is a really good research subject because its mountains and coastline provide a wide variety of watershed scenarios to teach the AI model.

There often aren’t enough water monitoring stations or funding to keep them going for as long as researchers need to understand the full picture of a watershed’s issues with nutrient pollution, Valladares Castellanos said. This has led to gaps in data needed to make accurate findings.

The hope is that, after training in the lab of Puerto Rico, the same AI tools can be used in other places like the Mississippi River Basin to prevent nitrogen and phosphorus from being washed down the Mississippi River and creating dead zones where fish and other aquatic life can’t survive.

“When you want to inform policy, you don’t want to have blind spots because then you might be inferring or creating assumptions that then might not apply to those areas that don’t have data,” Valladares Castellanos said.

Matthew Baker, a professor of geography and environmental systems at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, is using AI for his hydrology and restoration work in the Chesapeake Bay area. The technology can make something as complicated as a watershed a little bit easier to understand when trying to fix water quality issues, he said.

“The exercise now is to examine the many different ways that we can use artificial intelligence to augment our understanding, so not just the ability to predict better but also to understand with greater resolution, greater accuracy, why the watersheds are behaving the way they are,” Baker said.

With continued research and upping the complexity of the AI-informed model, Valladares Castellanos said tools like this could be used to better inform strategies to reduce the annual Gulf dead zone.

“We are always trying to get closer and closer to the real world conditions” and lessen the margin of error, she said. “This just gets us a little bit closer to that.”